City of Shadows

Published in The City is a Novel (Damiani, 2015)

Tuchkov Pereulok 12/12, St. Petersburg, 1996

During the sixties, my family had a small room of fifteen square meters in a communal apartment in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg). There I lived with my parents, grandmother, and aunt, who was then a student. I often disturbed them, mostly at dawn, because I woke very early and didn’t know how to keep myself occupied. The morning wait was unbearably boring—each moment seemed as long as a lifetime. To put an end to this situation, the adults taught me how to read. Reading affected me profoundly, stimulating my imagination and sensibility, giving me the desire to dream and especially to dream while taking walks. Reading also altered my vision of the surrounding reality, endowing it with mystery and intrigue.

It seemed to me that behind the buildings, trees, and certain objects in the street—streetlights, for example—something magical lingered. A burning desire to see the hidden aspect of things overtook me. At such moments, I experienced an excitement that I had never felt before: I sensed an invitation to discover an unknown substance, material or spiritual. These moments made me happy, so happy that upon returning home, to the humble reality of daily life, I could only think about one thing: how to capture these special moments so that I would have them at my disposal, and to render these instances into a permanent mode of life.

Around the same time, someone gave me an old, prewar camera, Komsomolets (meaning “Young Communist”). It was simple, even rudimentary for medium-format film, but to me it seemed complicated, impenetrable, yet at the same time promising: What if this black box could capture the brief moments of reality that made me so happy? I found the idea brilliant, so I coaxed my parents into signing me up for the children’s photography workshop at the Kirov Cultural Palace, just before my ninth birthday.

Dostoyevsky was one of the writers who sparked my desire to discover this hidden facet of things. After reading Poor Folk, Humiliated and Insulted, and Crime and Punishment, I was most attracted to the types of buildings where his characters lived: labyrinthine courtyards with multiple entries—sometimes with walls so high and narrow that you seemed to be in a well, dilapidated stalls, and places where the marginalized society was found, alcoholics, tramps. Leningrad, its historical sides and in particular Vasilyevsky Island, where I lived, was filled with such people. I spent entire days exploring such places.

Unfortunately, haunting these places didn’t enable me to create original images. The pictures that came out of the magical box were even less interesting than my surroundings had seemed to me before I learned to read. I couldn’t produce prints that aroused in me the same unique emotion I felt in the streets, and I attributed this failure to a technical imperfection, or my lack of photographic knowledge and education.

Disappointed, I continued nonetheless to read, and it did lead me to a discovery: François Arago’s famous speech announcing the invention of the daguerreotype and Louis Daguerre’s View of Boulevard du Temple (1838), taken with a very long exposure. The people had disappeared from Daguerre’s image except for the silhouette of a man who lifts up his foot probably to have his shoe polished. I didn’t try to imitate this photo. But I sought out more illustrated books and catalogues of French 19th-century photographs, especially street scenes, and I worked to improve my French.

Dostoyevsky was also instrumental in fostering my desire to know classical music. In his short story White Nights, the heroine (whom of course I fell in love with, just as the hero did) went to the opera to listen to Rossini’s The Barber of Seville and was enchanted. I tried the experience myself, and then bought a record. Little by little, I became a regular of the record shop and started to familiarize myself with a broad spectrum of classical music. Vinyl discs were expensive, and so were concerts. Later, by chance, when I was a student at the university, I was hired as an assistant to the administrator of the famous Grand Hall of the Saint Petersburg Philharmonia. There was at least one concert almost every day, and because I worked in the evenings I was able to stay in the hall and listen to many of them. The music sometimes created the same joy and excitement in me, as did particular corners of the city. Further, music offered me an emotional dimension to everything that presented itself to my senses. It invited me to interpret things without ideological color, in a more universal—a more humane and honest—way. It provided an escape from Soviet reality, where all arts were considered instruments of propaganda, and there was no space for the expression of an authentically personal sentiment.

I was initially inspired by Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Tchaikovsky: composers whose musical language was more accessible. However, I also listened to Shostakovich. At first spontaneously and then in relation to my personal history, I sensed the profundity and importance of his music: my parents and grandparents are survivors of both the Gulag (my father was born in a camp as the “Son of Enemies of the People”) and of the Nazi blockade of Leningrad. I was told in the Philarmonia that Shostakovich had lived in fear since the publication of an essay in Pravda called “Muddle Instead of Music,” written in 1936 after the premiere of his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. The essay denounced him as a “formalist,” which in the political climate of the time designated him as an Enemy of the People. Everyday he expected to be arrested. At the outbreak of the war, Shostakovich participated in the city’s defense before its evacuation, and in the words of the official press, he “commemorated the heroism of its inhabitants in his ‘Leningrad’ Symphony.”

Courtyard, Leningrad, 1975

Shostakovich’s works reflect two experiences shared by the entire Soviet population: the Stalinist Terror and the horrors of the war. Identical musical phrases convey the exact sensations that the composer experienced in 1937, when the Terror reached its peak, and in 1941, which are an expression of his sentiments toward both Communism and Fascism. In Symphony no. 7, the “Leningrad” Symphony, isn’t the part based on the repetition of the simple melody often known as “the invasion theme” as innocent at the start as it is cynical at the end? Does it speak only of invasion to us? Isn’t the journey from simplicity and innocence to cynicism and crime a journey that was taken by both Stalin and Hitler, as well as by the dictators of our own time? And more generally, doesn’t one hear the symbolic expression of evil? In this sense, Shostakovich’s message is universal. This is what propelled me to return repeatedly to his works, to “read” them, finally, while deciphering their real sense until they would become a part of myself.

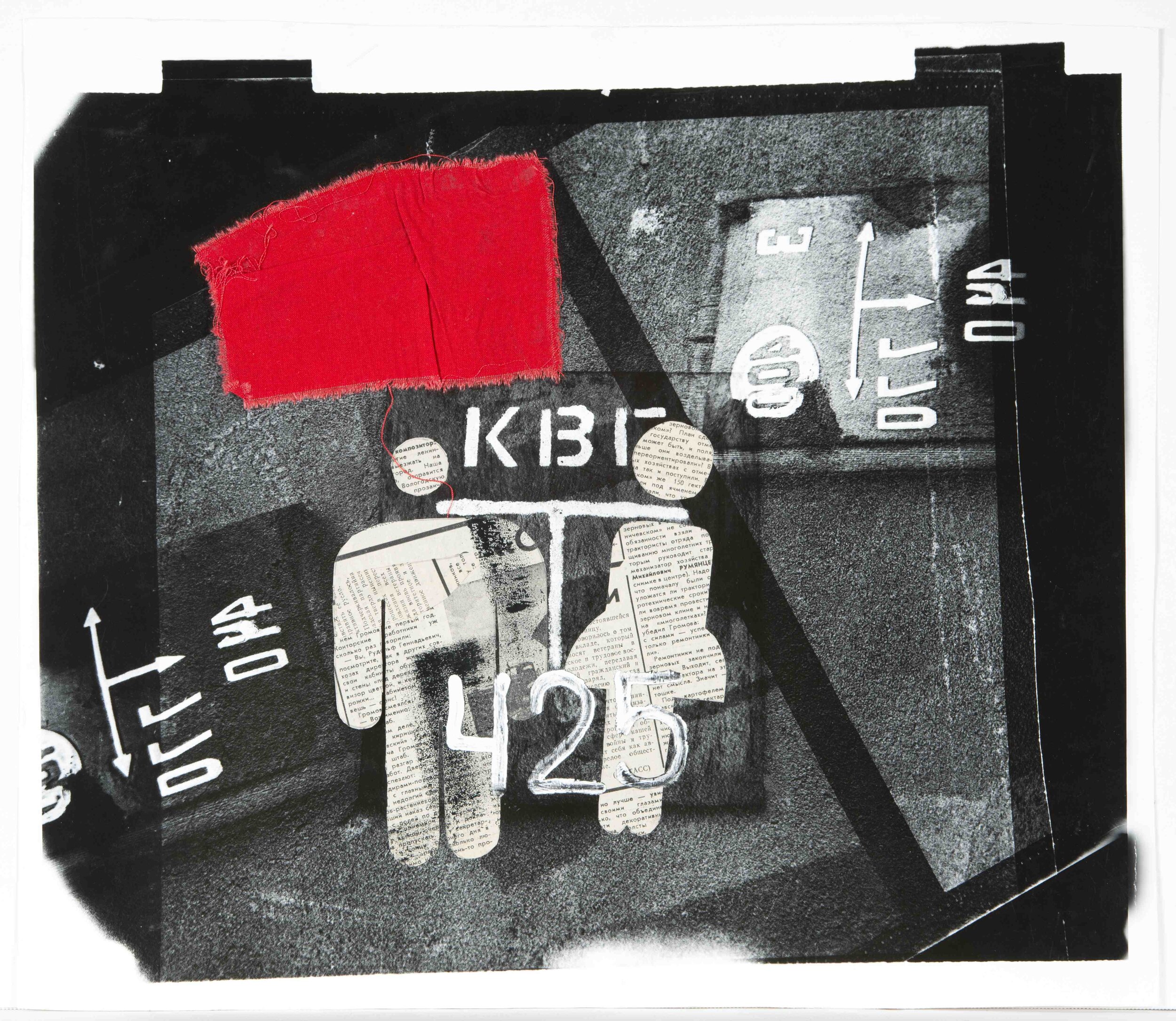

Collage from the series Leningrad from Another Side, 1979

To return to photography: with this underlying urge to capture happy moments, I created better photos—from the technical point of view—with a new camera, a Soviet version of a Leica. But the result, I still felt, was dull and disappointing. I began to suspect that this was caused, at least in part, by a flaw in the composition of my brain.

At the Kirov Cultural Palace, stubborn and persistent, I had begun to take classes in photojournalism, each day pushing a little further into the discipline and “perfection” of images. There, in a nearby room, a crowd of bearded men met every week, their bluish cigarette smoke with or without filter, invading the corridors. Though a non-smoker, I was accepted a year later as a full-fledged member of this “institution,” a photo-club, called “Zerkalo” (Mirror). What mattered most to the members of Zerkalo—an intelligentsia of musicians, engineers, doctors, and painters—was not just photography in itself, but photography as a means to reproduce or discover, for example, the works of nonconformist and anti-Soviet painters in Leningrad, and of contemporary Western art, which was not generally known, as well as forbidden and unobtainable literature, such as Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago or Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago, that could be read on microfilm. More important, one could, in Zerkalo, also read the reality of life inside the USSR as it really, truly was, without propagandist cosmetics. Moreover, one could have open and frank discussions.

At that time, what seemed most pleasing to me was that literature and poetry had the capacity to transform, by way of poetic comparisons or metaphors, a gloomy and uniform reality into something more appealing to the imagination and of its truest essence: to “embellish” reality with the emotional and personal experiences of the writer who can in turn bestow on the work an additional aesthetic value.

One day, toward the end of the seventies, my Zerkalo friends, knowing that I was fluent in French, asked me to translate Dawn Ades’ Photomontage, published in Paris by Éditions du Chêne. This book, by a professor at the Royal Academy in London, had a striking effect on me. I suddenly understood how photography could translate an artistic vision. And the use of metaphor was clearly to be found in Dadaist photomontages. Rushing to my archive of Dostoyevskian photos that I had previously found so worthless, I began to cut them with scissors and create compositions that would succeed as a series of photomontages, eventually entitled Leningrad from Another Side. For the first time, these creations, rather rudimentary to be honest, touched me, and not just me but also the bearded smokers of the photo-club. During the eighties, I continued to use the same process for a series of montages and photo collages, Nomenklatura of Signs.

Not only did literature provide me with material and subjects, it also helped me discover a process to translate and transform an internal and purely subjective state into something more durable and, above all, capable of being communicated to others.

Was it possible to convey a vision by means of photography? Could photography become a language that could articulate meaning? My response, thanks to this initial experience at the end of the seventies, was a resounding Yes. Consequently, I decided not to abandon photography but to devote my life to it by enrolling in the Faculty of Film and Photography at the local university to pursue a master’s degree.

Photomontage from the series Nomenklatura of Signs, 1986

Collage from the series Nomenklatura of Signs, 1987

Intense immersion in my studies, coupled with a job at the Philharmonia and the encounter with the first love in my life, obliged me to put aside my artistic projects and concentrate on getting my diploma. This was followed by military service, obligatory for graduates (even though it was shortened to eighteen months). One incident while I was in the military particularly affected my viewpoint on life and Soviet society. I was arrested by “Special Department” officials (representatives of the KGB in the army), and charged with several offenses, one of which was having “compared Communism to Fascism”—enough to send me to prison for many years.

I had not grasped the mentality of my fellow conscripts: most were only eighteen years old and came from the most diverse and remote places in the USSR. Steeped in propaganda and prejudices instilled since childhood, they perceived anyone who thought differently as suspect, fit to be denounced. My mail was intercepted, my words scrupulously reported to the “organs” (another euphemism for the KGB). I felt as if I were an actor in a staging of Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago, with so many scenes exactly as in the original text. I already knew some hidden truths about Soviet life, in the same way one knows that one will die someday and that “someday” could be tomorrow, without my life being affected in any way. But now I truly believed in these hidden truths.

In 1984 the system was already starting to fall apart. The regiment’s chief officers were absent on a mission elsewhere, and since I had in principle fulfilled my eighteen months of compulsory service, I obtained a demobilization order that was duly signed and stamped by an officer on temporary duty, who was surprised to learn that I had been detained in the garrison prison without an arrest warrant. I took the first bus at dawn and was back home the next day.

When I returned to “normal” life, the idea of articulating my vision of Soviet Russia began to seem more and more valid to me. I formulated the project like this: During the years of its existence, the Soviet regime had succeeded in installing the dominant power of the Communist party’s nomenklatura, as well as another nomenklatura in its image, that of signs. This means that the people living in the Soviet Union and their daily activities were replaced by hypocritical visual signs: posters, mural paintings, banners, and slogans of colossal dimensions. The representation of the reality of Soviet life was, in fact, considered a crime, which could lead to imprisonment, forced deportation to labor camps, or, in some cases, even the death sentence.

The seed of the project Nomenklatura of Signs was soon born in the form of images from superimpositions of several negatives or collages that mixed photographs, red tissue, excerpts from Brezhnev’s discourses, and so forth. These images constituted my visual landscape at that point in time, transcending all realistic references—a landscape in which individuals were reduced to simple caricatures: the “True Worker,” or the “Happy Builders of Communism.” Above all, this series was conceived as a reflex against the stupidity and absurdity of the Soviet regime: a personal reaction to the strange or even supernatural manifestations of the system.

Female worker (version 4) from the series Nomenklatura of Signs, 1987-89

Male worker (version 4) from the series Nomenklatura of Signs, 1987-89

In 1991, while Soviet totalitarianism was fading, I was still working on the Nomenklatura, but at a certain point I realized that I was debating with myself in a void, and that my work, while completely sincere, risked appearing as opportunistic. By now, Soviet people had been transformed into mere signs by an oppressive regime: their life was no more than a substitute for the real world. All these people conditioned by propagandist models of representation, a palpable ensemble of smiling faces, were becoming wandering shadows. The collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991 left most Soviet citizens with few means of survival. The situation became so drastic in Saint Petersburg that Germany sent humanitarian aid to avoid famine and premature deaths among the aged. Inhabitants of the city called this period the “second blockade.”

One day in the winter of ‘91-‘92, I was hanging around on a street in the center of town, a place that had once been cheerful and teeming with people. Now, on a late afternoon, it was barely lit and devoid of cars. In the eerie silence, interrupted only by the banging of doors in shops with empty display windows, I could hardly recognize these people, seemingly lost men and women, soberly dressed, their faces filled with fatigue and despair, breathlessly carrying out the daily search for some basic food to make a meal. They were like shadows—shadows that had not been seen in Saint Petersburg since the war and the blockade. The scene impressed me strongly, and I felt the need to communicate this distress and suffering to others—to express it through my photographs, and to let myself be carried away by a leap of humanity towards these habitants of the city of my birth. Such ill-treatment of human beings, victims of an extraordinary injustice throughout the twentieth century—this metaphorical representation of “men-shadows”—the pillar of my new vision—must first be conveyed through photography. Thus I chose a very long exposure time.

Crowd entering Vasileostrovskaya Metro Station, St. Petersburg, 1992

I vividly remember the first image, taken at the entrance to the Vasileostrovskaya metro station, located in an old neighborhood, surrounded by factories and shipyards. For the daily commute, the metro was the only public transport in service during this period of crisis. The train is deep underground—more than a two hundred feet—because the soil is so unstable, and access to the platforms is by way of a seemingly interminable escalator. When the escalator broke down, as often happened, entry to the station was restricted to avoid a dangerous crush. At rush hour a crowd of several thousand people would accumulate outside and in waves this human tide climbed up the stairs leading to the entrance of the impressive building on high ground, as was generally the case for most metro stations in Leningrad. Barricaded behind its glass doors, a few policemen were trying desperately to contain the masses of people. In vain, because the crowds were determined to enter at all costs, even if it meant losing a button or a shoe. People pushed, yelled, threw punches. Handicapped people were trampled. It was like a scene from hell.

As I watched, shocked and appalled, a musical air emerged in my head, a fragment of Shostakovich that brought me to tears. Not thinking consciously about what I would do, I set up a camera in front of the crowd. No one paid any attention. The exposure time exceeded several minutes and I pretended to wait, to read something in my notebook. Then someone jostled me and I closed the shutter. In the evening, looking at the negative, I experienced the same emotional shock I had felt when the Shostakovich melody came into my mind: deeply moved, almost in tears, but also filled with enthusiasm and excitement. Depicting the crowd as a general movement with erased secondary movements, the metaphor created by the long-exposure effect, made evident certain fixed elements that would otherwise have been drowned in an abundance of details and faces. Yet these were exactly the elements—hands on the stairway rail, for example—that moved me, provoking in me an intense emotional pain I felt at the time as well as a wave of love toward the crowd.

The mass of indistinct faces symbolized a precise moment that I had witnessed, but there was more to it. Similar episodes came to mind: wars and revolutions the Russians had suffered throughout their history. It was as if one photograph had embraced a decade, even a century. I felt that my childhood dream of capturing on film a state of the soul or a singular impression experienced in the street had come true—reality as I had felt and imagined it had been recreated. It was this notion of time—as if introduced in a slightly “mechanical” way while keeping the shutter open as long as possible—that transformed what would otherwise be just a simple “document” about a particular era into an actual visionary oeuvre.

Resolved to continue this work, I happened to notice some images grouped in a certain way on a table, and the idea of a project dawned on me: a new series entitled City of Shadows, based on my impressions described above. What guided me in constructing this ensemble was once again a musical piece, Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto no. 2. As I watched the ghastly scene at the metro entrance, the opening melody from the first movement overwhelmed my hesitations and freed me from doubt, from self-interrogation, and from a childlike fear, if not to say a sense of shame. It allowed me to confront the furious, menacing crowd.

This concerto soon became my best friend; I could listen to it all day, every day. As I walked in the city, I began to realize that Saint Petersburg again and again offered living illustrations for this music. The monotonous opening melody was that of despair, but also of anticipation. The way the piece was composed—a reminiscence of dramatic episodes of the composer’s adolescence, followed by baroque passages and moments throughout, with a certain drifting sensation of happiness—was decisive in the conception of several images. For example: old women hastily selling food and cigarettes to passers-by, trains, and people leaving for their dachas, as well as peaceful views of the rain falling on Nevsky Prospect, the city’s main avenue.

View of the Roofs, St. Petersburg, 1996

Attic, Kid Looking through the Window, St. Petersburg, 1993

The years passed. People wearied of this interminable descent into hell. The situation continued to worsen. Added to the shortage of necessities was the collapse of the healthcare system. Retirement became nonexistent. People vanished, as if they had secretly emigrated, or died. Crime invaded the city and spread. By the middle of the 1990s, Saint Petersburg was perceived more as a capital of organized crime than as a cultural center; a television series, Gangster Petersburg, was broadcast on a national channel. Like others, I was depleted and disappointed. Hopes raised after the fall of the USSR had not been borne out. Slowly, however, the survival instinct compelled me to search for things that could bring some sort of moral respite, if only briefly.

That’s how Dostoyevsky’s White Nights, which was merely a vague memory, caught my attention again, this time by pure accident. I was struck by a certain view from the kitchen window of our communal apartment, saturated with the smell of cabbages and dried apples. Years ago, as a Soviet schoolboy, I had read White Nights while contemplating this landscape of rusty roofs that extended to the horizon. The attics, the mosaic of windows, were each illuminated by a particular light, sometimes revealing a glimpse of faces or shadows on the curtains. A soft, golden light enveloped my reverie. I was moved, and for the first time in a long while I felt calm after having lived these last years in a constant and heightened state of nervous tension.

I was also seeking calm in classical music, comparing it persistently to photography, so that the former seemed to me richer and capable of articulating or expressing greater sentiments. Thanks to having accumulated a vast record library since my adolescence (which included some of the Second World War live concert radio recordings), I had come to discern the way in which the personalities and the visions of different artists could be translated through the interpretation of the same musical work. How, I asked myself at the time, could a famous pianist such as Grigory Sokolov or a legendary conductor such as Wilhelm Furtwängler, introduce through his own style a personal message that sounded new and independent of the composer’s? How could the musician touch our senses so that we could take a disinterested pleasure in discovering that message and consider it henceforth a form of beauty, even a new truth—and, in spite of this, to see it as a truth that came from ourselves?

Musicians could do this by creating distinct—sometimes sharply different—styles within a movement. To use an expression of Flaubert’s, they passaient au rabot, changing the tempo specified by the composer and playing a part of the score with swiftness, energy, so that the sounds, the particular phrases, blurred off, with the general movement overwhelming the details. Then, slowing down, they sometimes played certain notes, even several bars, with an intense and meticulous attention: a “neatness” in which they (or the entire orchestra) engaged every bit of their virtuosity. This new relationship between the parts that may, but doesn’t necessarily, correspond to the intention of the composer—isn’t this a creation in itself, an original idea that we owe to the performer?

I took pleasure in transposing the intervention of a musician into my shots, to reconstitute the effects of musical “virtuosity” and “neatness” by applying with a fine-art brush some bleaching solution on certain details: this application brightened them considerably and detached them from the rest of the image, which appeared as “blurred” or “drowned” into gray. Sometimes I would just give a certain figure in the image a more pronounced density, juxtaposing it within the pale, soft background of the surrounding landscape. The result obtained was similar.

In some way, the effect of a long exposure in photography is comparable to the methods of musical interpretation: the latter directs the listener’s attention to elements that might have gone unnoticed. In fact, it suggests precisely another meaning, which is more personal. All this gives music, as well as print, a poetic dimension that is the equivalent of metaphor.

Three Pensioners Selling Contraband Cigarettes, St. Petersburg, 1992

I realized at the time that this delicious shiver, more commonly known as goosebumps, the state of being overwhelmed by a wave of emotion, has to do with the great performer’s ability to lull the audience into a state in which what comes next is emotionally unexpected. Drowsy and appeased, the listener is surprised to hear a chord introducing an abrupt change of mood, experiencing a sensation of nouveauté, of beauty. Or the audience, exhausted, irritated by a chain of sounds that are expressively “vulgar” or “badly performed,” may feel a profound emotion arising when a passage of tender and baroque simplicity suddenly arises, a passage of music that in a different situation would pass for something banal.

The lesson I learned was that beauty is relative. To be accurate, only a part of the beauty resides in the object itself (for example, the execution of a melody), and the other part depends on the receptive listener, on his or her state of soul, memories, sensibilities.

Like a musician with his or her score, I must interpret each negative, considering it as a foundation on which to build, associating the work each time to a creation that is somewhat different, a new message that is unexpected by the public, avoiding weariness and preserving fresh perception so that each new print provokes at the very least a surprise, if not a shock. The challenge of keeping perception open and fresh stimulated my desire to play with the nuances of the states of the soul, and in broader terms, to consider the print itself as a musical piece. Why, for example, must an image always contain black and white—as was instilled in us through textbooks and classroom photography lessons? What about a piano piece that is only played on one part of the keyboard? The same melody could be played one octave lower or higher, thus creating a very different impression. I could play a new octave on print by making it on the paper that is previously slightly exposed to light, and not just on blank paper, thus allowing me to obtain a veil that is more or less gray. Minor or major key? This was conceivable by just leaving the gray image as it was, or by working delicately on some areas in the image (with the technique of partial toning) that would imitate a warm and gentle golden light, precisely the one that enveloped me when I was reading White Nights.

This peaceful sweetness, entwined with childhood and adolescent memories, was recalled to me by Dostoyevsky’s story. It aroused in me the desire to rediscover those districts of the city I had not visited for years, since my first attempt, in the late 1970s, to create an original work of art with a pair of scissors. I had to capture that magical moment of peace within myself while hopes of a better life were slowly receding. It was a vital experience and I was, from then on, better prepared. White Nights had indeed inspired me.

Woman on the Corner, St. Petersburg, 1995

One of Dostoyevsky’s ideas to which I adhere completely is the personification of houses. Each house has its own character. Clearly, they do not move about. Although they are stationary in relation to the camera, the camera can shift as I please when taking a picture of them during a long exposure time. It is the same with light, the sun playing an essential role in the narrator’s monologue in the middle of Dostoyevsky’s story: by displacing the camera, I could render it alive and magical, too.

Sunset on Canal, St. Petersburg, 2006

It was as if the sun had been waiting just for this. Already, on the very first negative, the sun’s rays started to smile at me by singing in C major! The technique I invented had also allowed me to recreate the ambience of the city at different moments of the day or night—or rather the white nights—and of reuniting them in a series of images in soft and pale colors, reminiscent of certain paintings by Whistler (who claimed Russia as his place of birth, even though he was born in Massachusetts). This particular series would be entitled “Black and White Magic of Saint Petersburg.”

A year later, in 1996, although nothing had truly changed in the country, I had the privilege of seeing this series hung on the walls of the City Exhibition Hall. The present and the future began to show themselves to me in a more favorable light. Revitalized, my spirits searched for optimistic notes in the current reality. My technical work improved greatly, and the sun, whose presence was more or less underlined by a palette nuanced by warm shades, dominated several prints.

In August 1998, a terrible crisis shook the country once more. The national currency, the ruble, became mere paper in just a few days. The collapse of the economy buried the aspirations of Russian citizens, their savings lost because of failed banks. The population poured out into the street. Some begged, some turned to prostitution, others hastily set up shop with all they could sell or trade: gold, milk powder, watches, onion bulbs, jewelry, cigarettes, porcelain, matches, bronze sculptures, worn shoes, potatoes, old books. This ongoing chaos transformed the entire city into an immense black market. Two very different photographs, one of which reveals the opposite of the other, symbolized this period: “A View of the Sennaya Square,” created a few days after the beginning of the crisis, and “A Begging Woman” taken a year later.

Hay Market Square from the Rooftop, St. Petersburg, 1998

Photographed from the roof of a house, the first shows Sennaya Square (Hay Market Square), which is emblematic of Saint Petersburg. In his early works, Dostoyevsky used this neighborhood as the home of many of his characters. Returning after years of imprisonment and exile, he settled near the square, and there, in an apartment on Malaya Meshanskaya Street (now known as Kaznatcheyskaya Street), he dictated Crime and Punishment to the woman who later became his wife. Raskolnikov’s murder of the old pawnbroker takes place not far from the square.

After Dostoyevsky’s death, and especially during the Soviet era, Hay Market was transformed. The Russian Orthodox Church that dominated the square’s southeast corner was demolished and later replaced by metro and bus stations. More crucially, the square ceased to be what it had always been: a marketplace. Within a year of the USSR’s disintegration, poverty, famine, and the explosion of crime had brought more changes than the preceding forty years. Beggars, prostitutes, vendors of smuggled goods, and small stalls filled the square’s immense space, turning the historic place back into what it had once been: a site of ill repute, a large market of dark dealings, a zone of illegal exchanges in broad daylight.

Toward the end of 1998, this neighborhood saw some revitalization. Small stalls were replaced by more civilized kiosks. In summer, when most of the city’s population escapes to the country, the square becomes almost empty. This is especially true in mid-August, when fruits and vegetables begin to emerge in people’s gardens. However, on the day when “A View of the Sennaya Square” was taken, everything was very different. Ordinary Russians were abandoning their dachas and gardens and returning to the city to buy whatever was available before it was too late, with money that was losing its value by the minute. This is the moment that corresponds to the photograph. There remains, however, a small detail in the center of the image: a couple—perhaps two young lovers—immobile in what seems like a kiss. This detail marks a huge departure from the past. The couple contributes a more romantic atmosphere to this image—an atmosphere less desperate than in the preceding City of Shadows series.

Begging Woman, Hay Market Square, St. Petersburg, 1999

The other photo, “A Begging Woman,” was taken a year later in the same place, but from another angle, at the level of the muddy pavement. In the twilight of a damp, foggy evening at the end of autumn, I was passing by the market. An old woman was sitting in the middle of the sidewalk covered by viscous brown mud. People walked past her without paying any attention. Around her, all was gray and gloomy. What attracted me to her was a piece of paper she was holding in her hand. The paper was very clear, almost shining, catching the last rays of light. It seemed to be the mirror of her soul, a cry of distress. It bore this message: “For the love of God, please, help me.” One of the main ideas that I wanted to highlight in this particular print was the old woman’s solitude. To capture that, I had to create an ambience of confinement around her—a kind of dense smog, clouding the image at its edges. Naturally, for this poor elderly pensioner reduced to life on the streets, forced to beg from passers-by, a sentiment of compassion would overwhelm the beholder.

If there is compassion, there must also be love and understanding. And perhaps it is with these qualities that a person can reunite himself with one of the roles of an artist and one of the functions of art.

But I must return to the desperate attempt of my younger days to carry away and preserve moments that procure for me happiness—moments of moral and physical euphoria I know from my walks after reading. I allow these experiences to settle within me, and have exteriorized them and made them accessible through photographic images—images that have been exhibited in galleries and published in books. An idea comes to my spirit abruptly: is the city itself the genuine subject? Most often it barely appears. The main focus is not its iconic sites. Instead, can we not see emotions weaving and shaping the perception of the world in a profound way? My emotions? Yes, and also through me the emotions of those who have lived in this country and endured so many horrors, catastrophes, sufferings, these millions of anonymous people it was always considered proper to represent only from without.

Universal emotions perpetuated during the last century, like those that stir in us at the music of Shostakovich or the words of Solzhenitsyn and Pasternak, are the emotions that constitute the main themes of my photographs, to the extent of transforming the most documentary among them into elements of a novel—not reportage, but a novel, whose central theme is the human soul, its modulations inspired by gazing upon human events, with their vibrations in a major or minor mode.